Bigo Live Hack 2020 - Gratuit Bigo Live Diamonds & Beans [[IOS /// ANDROID]] * NEW *

Bigo Live Hack 2020 - Gratuit Bigo Live Diamonds & Beans IOS /// ANDROID * NEW *

Bigo Live Hack 2020 - Gratuit Bigo Live Diamonds & Beans IOS /// ANDROID * NEW *

Il en va de même pour Bigo Live Hack. Bien que l’industrie du jeu n’existe que depuis quelques décennies, elle a produit de plus en plus d’énergie et d’influence, et son industrie évolue plus rapidement que d’autres industries. On ne peut pas surestimer le fait que, lorsque nous jouions sur l'ordinateur central du FC dans les années 1980, nous ne pouvions pas imaginer que les chefs-d'œuvre 3A d'aujourd'hui puissent montrer autant que les peintures de chefs-d'œuvre de films hollywoodiens. Visage et expérience.Récemment, PLAYSTATION a inauguré le 20e anniversaire de la célébration, née à l'origine pour diverses raisons. La marque hôte actuelle, florissante, est devenue une grande famille, apportant une joie innombrable aux joueurs post-80 et post-90 jouent la série PS de grandir hôte.

Et PS a également attiré de nombreux joueurs, même des joueuses, qui n'avaient jamais joué à des jeux, tels que la célèbre série Xu Da Warfare sur Sony Host, qui a lancé trois séries sur PS1, qui constituent toutes une collection de toutes sortes de jeux rigolos. Tout le monde peut facilement commencer et s'amuser avec eux. De tels jeux ne pouvaient pas être imaginés pour apparaître sur Nintendo Host à cette époque.

Bigo Live Hack - Obtenez des diamants et des haricots illimités (version 2020)

Bigo Live Hack 2020 - Diamants et haricots illimités (100

Army Men Strike Cheats - Army Men Strike Hack

Army Men Strike Cheats - Army Men Strike Hack

Army Men Strike Cheats - Army Men Strike Hack

Vous êtes-vous déjà demandé pourquoi ce jeu avait un entretien? Ou que diriez-vous de comment faire l'entretien DISAPPEAR? Cela vous dira comment!Army Men Strike Hack! Obtenez gratuitement de l'or avec ces astuces pour iOS et Android! Fonctionne en 2020!

Dans cette vidéo, je vous présente le fonctionnement de Army Men Strike Hack. J'ai décrit chaque étape que l'utilisateur doit effectuer pour télécharger les astuces Army Men Strike. Ce mod apk Army Men Strike n'est pas simplement un autre faux outil en ligne. C'est une fraude 100

Who will win the March 2018 Italian general election?

Who will win the March 2018 Italian general election?

A geographical analysis, with maps

Thanks to the passage of the new Italian Electoral law of 2017 — colloquially known by the charming pseudo-Latin name “Rosatellum bis” —the country’s electorate now finds itself in possession of a shiny new voting system, which it will get the chance to try out for the first time on March 4, 2018 when simultaneous elections will be held for the upper and lower houses of the Italian parliament.

The new system is the result of a long process of negotiation and compromise between the parties of the centre-left and centre-right that make up Italy’s current coalition government. The system it sets out works by ensuring that each vote is counted twice: once as a proportional vote and once as a plurality one, with around two thirds of the seats in parliament being allocated using the proportional system and around one third using the plurality system.

Proportional and plurality electoral systems

In a perfectly proportional electoral system the whole of a country is treated as a single constituency and each party is allocated seats in parliament in proportion to the percentage of the vote that they receive. For example, if a party gets 20% of the vote then it should get 20% of the seats.

In contrast, in a plurality (or “first-past-the-post”) electoral system a country is divided into multiple constituencies, and the seat in parliament corresponding to each such constituency is given to the candidate who receives the highest absolute number of votes in there. For example, if the candidate with the highest number of votes in a constituency gets 20,000 votes then they win the seat, regardless of whether that was 80% or 20% of the total votes cast.

The results of proportional elections are relatively straight-forward to predict, as a party’s representation in parliament will be equivalent to its percentage share of the national vote. The results of plurality elections are more difficult to predict. This because the only thing that matters in such a system is who gets the highest number of votes in each geographical constituency, meaning that relatively small changes in the number of votes a party receives can have a magnified effect if they occur in the right place.

In a two-party system, like that of the United States, this difference is usually pretty theoretical: if only two candidates are running then the one who gets the most votes will also have a majority, by definition.

In multi-party political systems, like those of Europe, the difference is far more significant. For example, the 2017 UK general election — which was carried out using a pure plurality system —resulted in the following anomalous results:

- The Liberal Democrats got 7.4% of the popular vote but only 1.8% of the seats in parliament.

- The Democratic Unionist Party got 1.5% of the seats in parliament — almost the same as the Liberal Democrats — with only 0.9% of the popular vote.

This was possible because votes for the Liberal Democrats were spread relatively evenly across the whole of the UK, meaning that there were very few constituencies in which they had more votes than any other single party. In contrast, the Democratic Unionist Party did as well as it did because all of its support was was concentrated in a small geographical area — all within Northern Ireland — where it often had more support than any other single party.

In sum, in a plurality electoral system geographical vote distribution is very important.

Rosatellum bis

The new Italian electoral system works by combining proportional and plurality systems, with 61% of seats in parliament being allocated proportionally, 37% being allocated using a plurality system and 2% being chosen by Italians living abroad.

The system allows parties to present themselves in elections either individually or as part of a coalition. In the case of a group of parties presenting themselves as a coalition, they must agree on a single candidate to put forward in each plurality constituency.

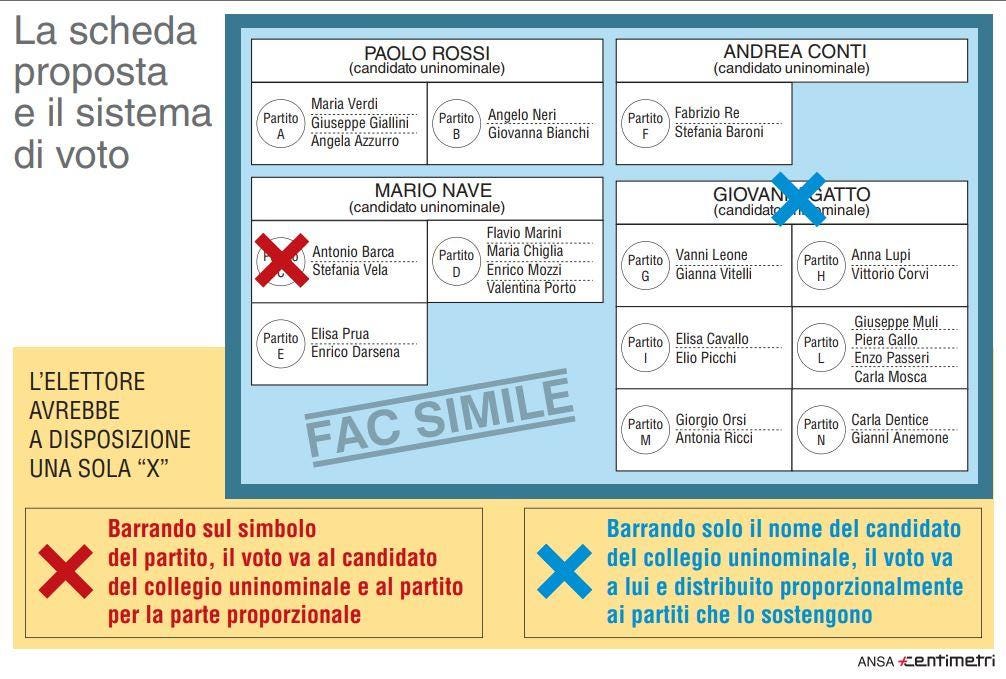

Each voter receives a ballot containing a list of plurality constituency candidates with a list of the party or parties that support them written immediately below it. The voter can then cast their vote in either of the following ways:

- By making a mark on a specific party symbol: in which case their proportional vote will be allocated to that party and their plurality vote will be allocated to that party’s indicated plurality candidate, whether or not that candidate is a member of the party that the person has selected.

- By making a mark on a specific plurality constituency candidate: in which case their plurality constituency vote will be allocated to that candidate and their proportional vote will be split evenly between the parties supporting that that plurality constituency candidate.

In the case of a voter marking a party and a plurality candidate who are not from the same party or coalition, the vote will be declared null and void.

Geography

In order to get some idea of how the Rosatellum plurality system will distribute parliamentary seats across Italy, we will start by looking at the geographical form of the country:

Now, let’s add some voters. The following map is manipulated so that the different areas of the country are resized according to the number of people who live in them:

Looking at this map, we can draw a few conclusions:

- The Italian population is spread reasonably evenly across the country. So just winning in say, the North, will not be sufficient to get a majority in parliament.

- There are a few densely-populated urban areas which are of disproportional importance relative to their geographical size. The most significant of these conurbations are Milan, Naples and Rome .

- There are some sparsely populated areas, particularly in the South, which are politically unimportant relative to their geographical size. Principally in Calabria and Sardinia.

Vote concentration

As regards the 61% of parliamentary seats that are allocated using proportional representation under Rosatellum bis, the geographical distribution of seats is unimportant. I.e. 20% of the vote will get a party around 20% of the seats in parliament regardless of how those votes are located geographically.

This is emphatically not the case, however, for the 37% of seats allocated to plurality constituencies, for which the only thing which matters for a candidate is getting more votes than any other candidate in that constituency.

As an example of historical vote distribution, we’ll now take a look at four maps illustrating the geographical distribution of votes received by the major parties in a recent election: that for the European Parliament in May 2014.

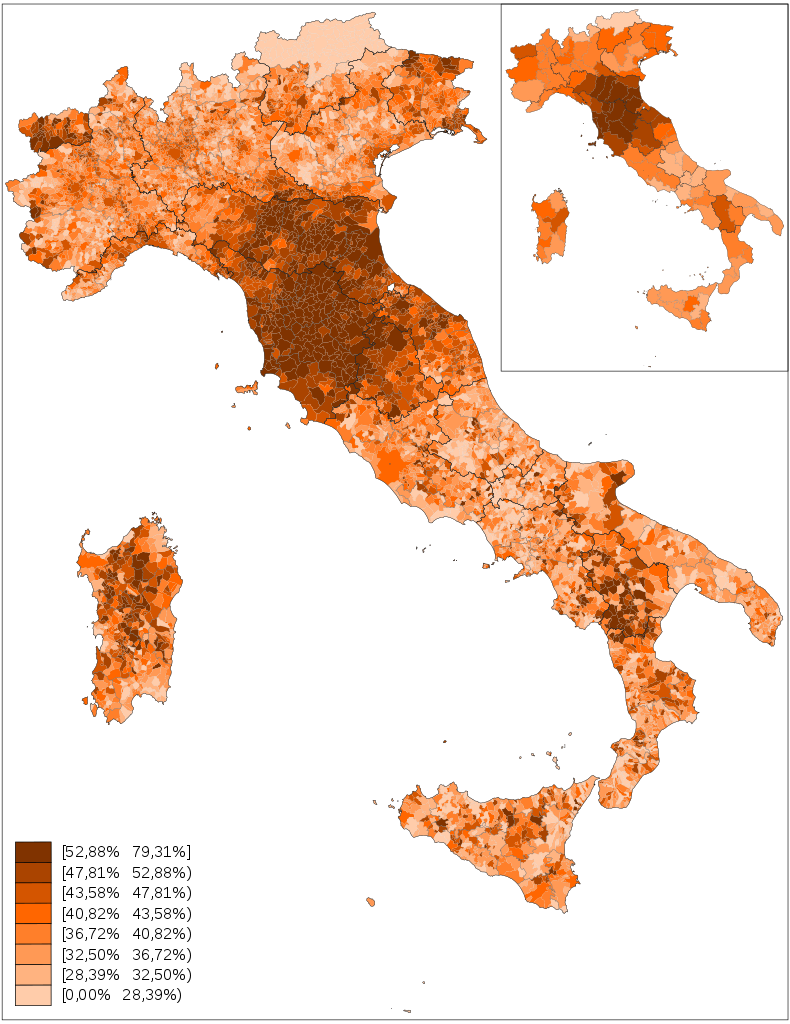

The Partito Democatico (PD)

The most successful party in that election — getting some 40.81% of the vote — was the centre-left Partito Democratico (PD, “Democratic Party”). As can be seen from the map they have support across much of the country, but it is concentrated in central Italy, in particular in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna. The party’s level of support is also relatively strong in the major cities of the North, such as Milan and Turin.

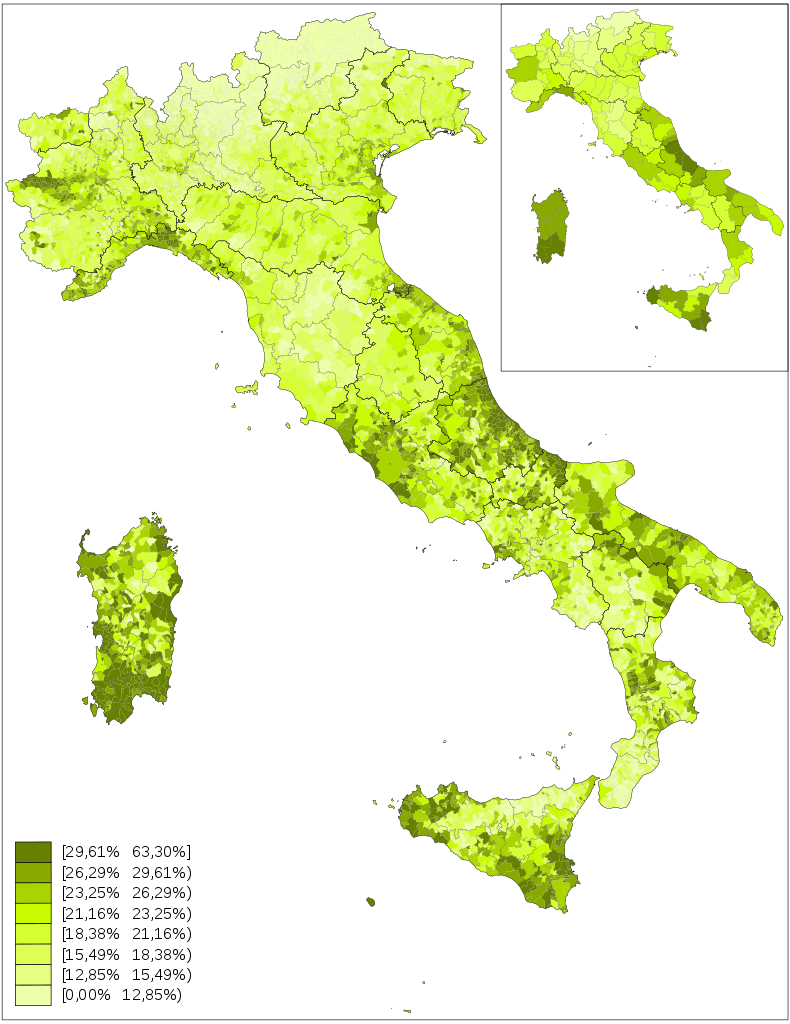

The Movimento Cinque Stelle

The second most successful party — with 21.15% of the vote — was the anti-system Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S, “Five Star Movement”). Again, the party’s vote is spread across much of the country but is strongest in a few scattered areas, including Sicily, Liguria and Abruzzo.

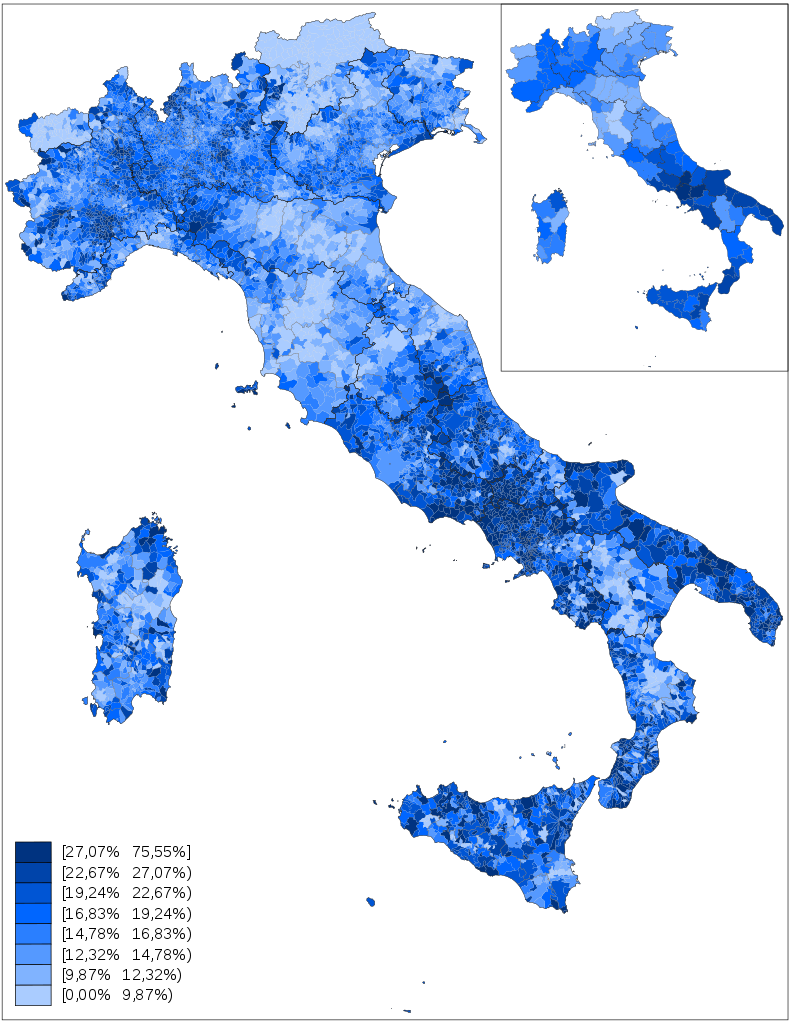

Forza Italia

The third most successful party — with 16.81% of the vote — was the centre-right Forza Italia (FI, “Go Italy”). The party has support across the country, but it is focussed in the South (in Naples, Sicily and Apulia) and the North West (in parts of Lombardy and Piemnote).

The Lega Nord

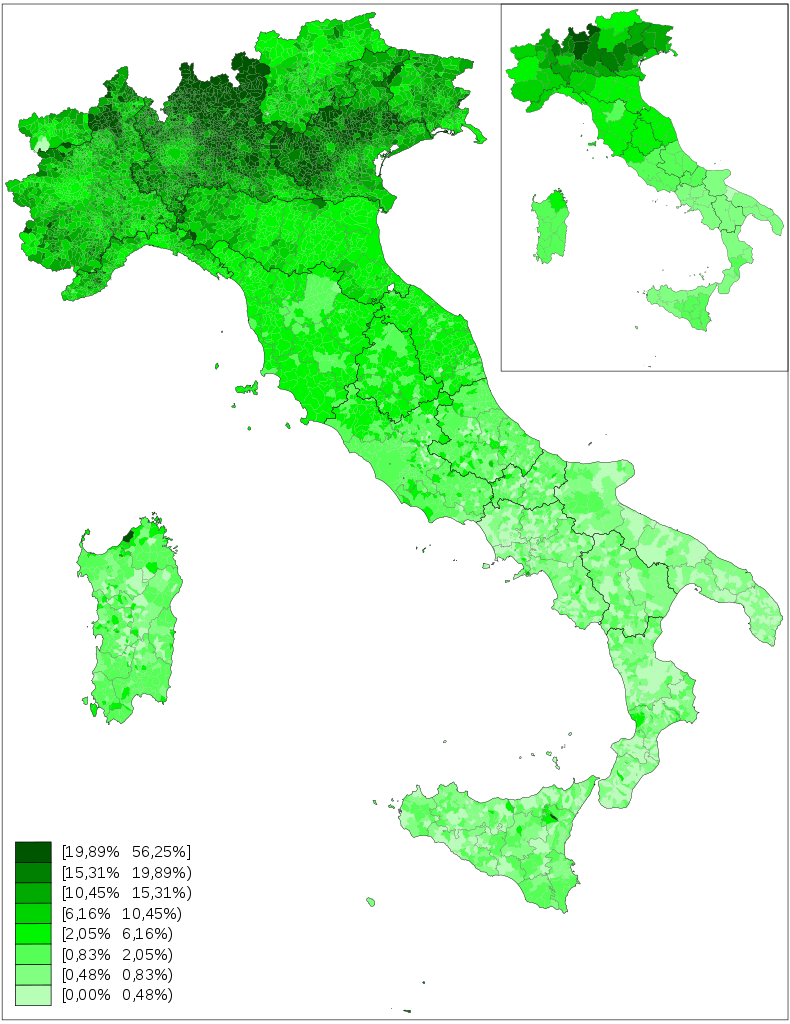

The fourth most successful party — with 6.15% of the votes — was the right-wing regional Lega Nord (LN, “Northern League”). This party was born as a regional separatist party calling for the North of Italy to break away from the rest of the country to form the independent republic of “Padania”, so its vote was unsurprisingly concentrated in that area. Within the North its support is particularly strong in rural Lombardy and Veneto, but is far lower in major urban centres such as Milan and Turin.

It’s the counting that matters

These 2014 European elections provide a neat illustration of the importance of different vote counting systems to the results of an election.

In reality the votes were counted using a proportional system meaning, for example, that the PD’s 40.81% of the vote translated into a fairly representative 42% of the Italian seats in the European Parliament.

In contrast, had a simple party-plurality system been used to count the votes, the result would have been those shown in the following map:

One hundred and four of Italy’s 107 provinces returned a plurality for the PD (the areas coloured red in the above map), meaning that they would have received 97% of the Italian seats in the European parliament — more than double what they received under a proportional system of seat allocation — had a plurality system of vote allocation been used in the election.

Coalitions

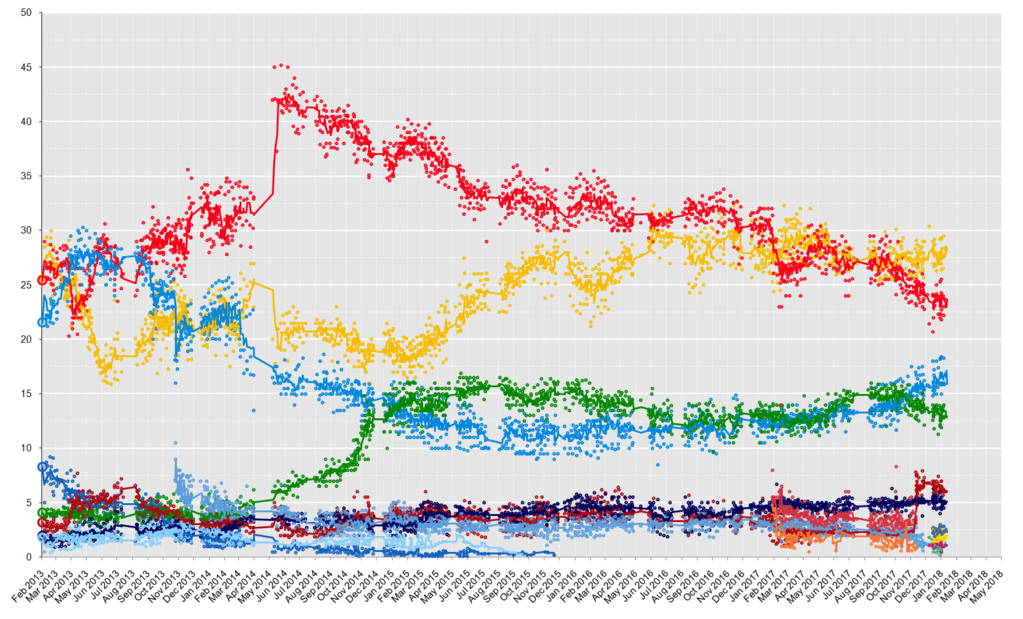

In the March 2018 election the PD has chosen to run in a coalition with a number of other small centre and centre-left parties, the M5S has chosen to run alone and FI and LN have chosen to run in coalition together with one other small, far-right party. This coalition of the third and fourth largest parties — together with the changes in voters opinions about the various parties which have taken place in the intervening four years — have made a big change to the predicted outcome of the March 2018 Italian general election.

Recent opinion poles foresee the centre-left coalition winning 25–28% of the vote, the M5S winning 26–28% and the centre-right coalition winning 35–37%. While it’s important to note that any of these figures could easily be out 5% in either direction — meaning that it would be quite possible for the centre-left to outperform the centre-right or for the M5S to outperform both of the coalitions — these polls do imply that the centre-right will be in a strong position when it comes to capturing the 31% of seats allocated using the plurality system.

However, as we have seen from the maps above, the absolute number of votes received is only half the story when it comes to determining how seats are allocated in a plurality system. Geographical vote concentrations can be equally important.

In broad geographical terms, the FI and LN should work well as coalition partners, because their support is spread across different areas of the country. The LN’s support base is in the Central North, while the FI’s is in the South and North West. Accordingly, FI candidates in the South and North West should be able to gain a few crucial percentage points of support from LN voters and vice versa for LN candidates in the Central North.

A variety of geographical factors, however, point to the centre-right coalition being unable to dominate plurality constituencies across the whole of Italy.

The first of these is the concentrated area of support for the PD across a wide belt that cuts through Northern-central Italy from Tuscany to Emilia-Romagna. Around 20% of the Italian electorate live in this area and other “safe” PD areas where the vast majority of the plurality seats there are likely to go to the centre-left coalition.

The second is the concentrated support for the M5S in a number of pockets spread across the whole of Italy, from Sicily in the South to Piemont in the North, where perhaps another 15% of the Italian population live. If the M5S is polling around 28% nationally then it is likely to gain a plurality in numerous such areas.

Thirdly, many areas of the country lack any clearly dominant political force (the areas that are relatively pale in all of the above vote-distribution maps), meaning that winning a plurality there will be entirely possible for at least two of the centre-right, centre-left or M5S. Perhaps another 20% of Italians live in such areas. It is improbable that all of them will go to the centre-right.

Accordingly, it seems reasonable to assume that the centre-right will not win more than 66% of the plurality constituencies.

An optimistic estimate for the right

Taking the most optimistic figures for the centre-right from what’s written above we get: 37% (maximum predicted vote share according to opinion polling); 66% (maximum predicted percentage of plurality seats that they can win); and 50% (an optimistic assumption of the percentage of foreign votes that will go to them).

Putting all of these numbers together we get:

- Actual proportional share of plurality seats in parliament: 61%

- Estimated centre-right total vote share: 37%

3. Estimated proportion of vote going to parties getting less than the minimum threshold required to enter parliament, which will then be re-allocated to more successful parties and coalitions: 10%

3. Actual plurality share of seats in parliament: 37%

5. Estimated centre-right share of plurality seats: 66%

6. Actual percentage of international seats in parliament: 2%

7. Estimated share of international seats going to the centre-right: 50%

Estimated total centre-right vote share = (0.61 * 0.37 * 1.1) + (0.66 * 0.36) + (0.5 * 0.02) = 0.495 ≈ 50% of the seats in parliament

If we are even more generous and assume that the centre-right will get 40% of the popular vote — three percent more than any of the opinion polls have predicted they will receive — these figures don’t change much:

Estimated total centre-right vote share = (0.61 * 0.37 * 1.1) + (0.66 * 0.36) + (0.5 * 0.02) = 0.516 ≈ 52% of the seats in parliament

Either of these figures would ensure that the next prime minister could be chosen (or at least vetoed) by the centre-right coalition parties and would certainly make them the dominant force in parliament, but neither would be enough for them to govern alone.

Perfect bicameralism?

One reason for this inability to govern alone with 50–2% of the seats in parliament is that it would only require a very small faction of of the centre-right coalition to vote against the government — or to abstain from voting — for its legislation to be blocked. A second important reason is the Italian parliament’s system of “perfect bicameralism”.

Perfect bicameralism means that all legislation must receive majority approval in both the upper and lower houses of the Italian parliament in order for it to become law. From this it follows that a functioning government will require a majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.

Under the Rosatellum bis the composition of the upper and lower houses should be quite similar: members of both are elected at the same time, from the same selection of parties and coalitions, following the same electoral campaign and using the same vote counting system. However, given that different candidates are running for the two houses, that the senate uses multiple regional constituencies to allocate proportional votes rather than a single national one and that the senate contains a small number of Senators for Life who are appointed by the president rather than being directly elected, it seems safe to assume that there will be a difference of a few percentage points between the different coalitions’ representation in the two houses.

Putting those two considerations together, the real bare minimum of seats required for a winning party or coalition to govern alone is probably around 53.5% of the seats in parliament overall. For example, getting 52% one house and 55% in the other.

Conclusion

Given that proportional representation is the dominant method of seat allocation in the new Italian electoral system and that support for the different parties and coalitions competing in the 2018 election is unevenly distributed across the country, in order for any party or coalition to get an outright majority in parliament it would need to at least equal the 41% of the vote won by the PD in the 2014 European elections.

Assuming a margin of error of 5% on current opinion polling results for Italian parties it is just possible for the centre-right coalition to achieve that, but not for any of the others. Accordingly, it seems probable that the next Italian government will be either a coalition of the centre-right, the centre-left or the M5S in coalition either with one another or with one or more smaller parties.